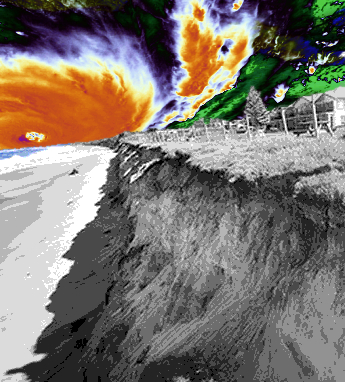

Weather twins can crush coasts

Increasing severe El Niño and La Niña events will cause more storms that lead to extreme coastal flooding and erosion across the Pacific Ocean, a new study says.

Increasing severe El Niño and La Niña events will cause more storms that lead to extreme coastal flooding and erosion across the Pacific Ocean, a new study says.

“This study significantly advances the scientific knowledge of the impacts of El Niño and La Niña,” said Patrick Barnard, USGS coastal geologist and the lead author of the study.

“Understanding the effects of severe storms fuelled by El Niño or La Niña helps coastal managers prepare communities for the expected erosion and flooding associated with this climate cycle.”

The impact of the twin storm system is not currently included in most studies on future coastal vulnerability, which tend to focus on sea level rise.

But the new data from 48 beaches across three continents bordering the Pacific Ocean suggests the forecast increased storm activity will exacerbate coastal erosion even without sea level rise.

Researchers from over a dozen institutions - including the US Geological Survey, University of Sydney, the University of New South Wales and the University of Waikato (New Zealand) – went back over coastal data from the Pacific Ocean basin from 1979 to 2012.

Data came from beaches in the United States and Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, and allowed scientists to determine if patterns in coastal change could be connected to major climate cycles.

The researchers determined that all Pacific Ocean regions in the study were affected during either an El Niño or La Niña year.

When El Niño was affecting the US mainland and Canada, Hawaii, and northern Japan - bringing bigger waves, different wave direction, higher water levels and/or erosion - the opposite regions near New Zealand and Australia saw “suppression”, which brought smaller waves and less erosion.

Then, the experts say, the pattern flips, so that during La Niña the Southern Hemisphere experienced more severe conditions.

The study also looked at related climate cycle changes like the coastal response to the Southern Annular Mode. They found that it impacts at the same time in both hemispheres of the Pacific.

The data suggests that if the Southern Annular Mode is trending towards Antarctica, wave energy and coastal erosion in New Zealand and Australia increased, and the same effects were seen along the west coast of North America.

Professor Andrew Short from the University of Sydney - a co-author of the paper - says that as global climate change creates an increase in the strength of El Niño and La Niña weather events, coastal erosion on many Australian beaches would be worse than the impacts of sea level rise alone.

“Coastlines of the Pacific are particularly dynamic as they are exposed to storm waves generated often thousands of miles away. This research is of particular importance as it can help Pacific coastal communities prepare for the effects of changing storm regimes driven by climate oscillations like El Niño and La Niña. To help us complete the puzzle, for the next step we would like to look at regions of the Pacific like South America and the Pacific Islands where very limited shoreline data currently exists,” said UNSW researcher and co-author of the paper Mitchell Harley.

“It's not just El Niño we should be concerned about,” said co-author Ian Walker, professor of Geography at the University of Victoria.

“Our research shows that severe coastal erosion and flooding can occur along the British Columbia coast during both El Niño and La Niña storm seasons unlike further south in California. We need to prepare not only for this winter, but also what could follow when La Niña comes.”

The full paper is published in Nature Geoscience, and is accessible here.

Print

Print