UK allows embryo editing

UK scientists have gained regulatory approval to genetically modify human embryos.

UK scientists have gained regulatory approval to genetically modify human embryos.

It marks the first time formal regulators have approved the use of the DNA-altering technique in embryos.

The research will be undertaken at the Francis Crick Institute in London.

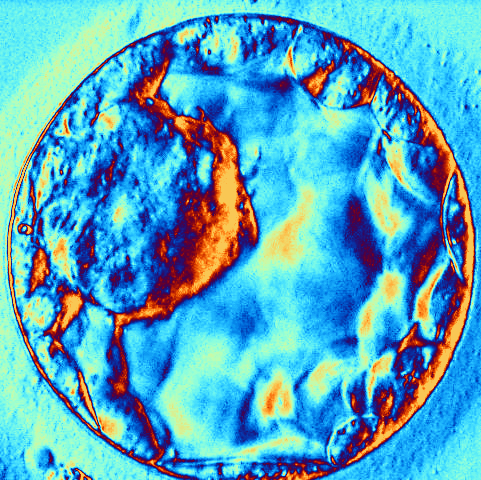

The scientists are only allowed to study the embryos in the first seven days of their existence, at a time when they consist of a clump of up to 200 cells.

It would be illegal for the team to implant the modified embryos into a human.

Still, they hope their studies will help provide a deeper understanding of the earliest moments of life.

Chinese scientists last year drew controversy for using the CRISPR gene-editing system in human embryos to correct a gene that causes a blood disorder.

But Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, a scientific advisor to the UK's fertility regulator, says things are different outside China.

“China has guidelines, but it is often unclear exactly what they are until you've done it and stepped over an unclear boundary,’ he said.

“This is the first time it has gone through a properly regulatory system and been approved.”

Dr Kathy Niakan will lead the work at Francis Crick, after spending more than a decade researching human development.

“We would really like to understand the genes needed for a human embryo to develop successfully into a healthy baby,” she said earlier this year.

“The reason why it is so important is because miscarriages and infertility are extremely common, but they're not very well understood.”

Some parts of our DNA are highly active even when an egg is freshly-fertilised, but for the most part it is unclear exactly what they are doing.

The UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has allowed researchers to alter particular genes in donated embryos, before destroying them after seven days.

“I am delighted that the HFEA has approved Dr Niakan's application,” said Francis Crick director Paul Nurse.

“Dr Niakan's proposed research is important for understanding how a healthy human embryo develops and will enhance our understanding of IVF success rates, by looking at the very earliest stage of human development.”

Dr David King, the director of Human Genetics Alert, is concerned.

“This research will allow the scientists to refine the techniques for creating GM babies, and many of the government's scientific advisers have already decided that they are in favour of allowing that,” he told the BBC.

“So this is the first step in a well mapped-out process leading to GM babies, and a future of consumer eugenics.”

Dr Sarah Chan from the University of Edinburgh said it was up to the regulator.

“The use of genome editing technologies in embryo research touches on some sensitive issues, therefore it is appropriate that this research and its ethical implications have been carefully considered by the HFEA before being given approval to proceed,” she said.

“We should feel confident that our regulatory system in this area is functioning well to keep science aligned with social interests.”

Print

Print