Tearing tests of skin-deep strength

Engineers have used some high-tech devices to find out why human skin is so resistant to tearing.

Engineers have used some high-tech devices to find out why human skin is so resistant to tearing.

Using powerful X-ray beams and electron microscopy, researchers made the first direct observations of the micro-scale mechanisms that allow skin to resist tearing.

They found four specific mechanisms in collagen - the main structural protein in skin tissue - that act together to diminish the effects of stress: rotation, straightening, stretching, and sliding.

The team from the University of California say they hope to use similar mechanisms in synthetic materials to increase strength and provide better resistance to tearing.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Skin consists of three layers - the epidermis, dermis and endodermis. Mechanical properties are largely determined in the dermis, which is the thickest layer and is made up primarily of collagen and elastin proteins.

Instead, the tearing or notching of skin triggers structural changes in the collagen fibrils of the dermis layer to reduce stress concentration.The research team began their work by establishing that a tear in the skin does not tend to spread or induce fracture, unlike other materials such as bone or tooth.

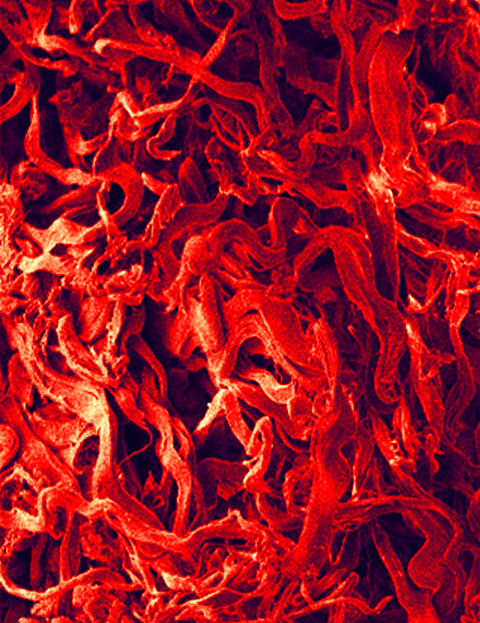

Initially, these collagen fibrils are curvy and highly disordered.

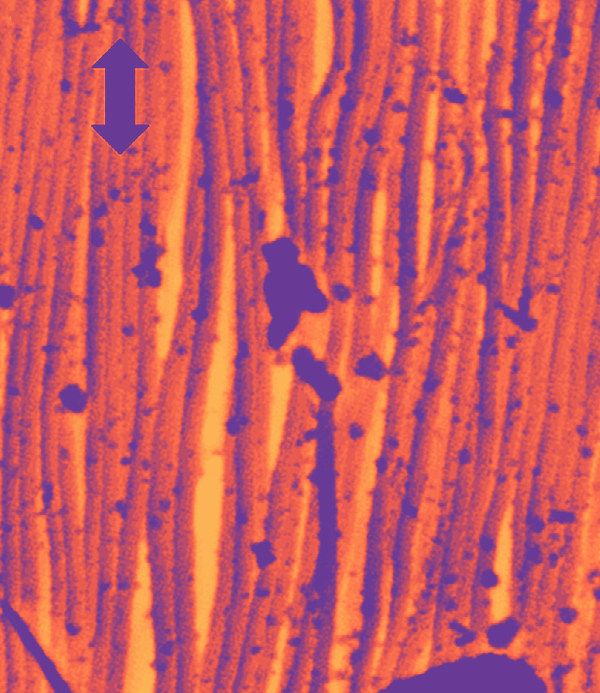

However, in response to a tear, they rearrange themselves in the direction in which the skin is being stressed, and prevent failure through rotation, straightening, stretching, sliding and delamination prior to fracturing.

“The rotation mechanisms recruit collagen fibrils into alignment with the tension axis at which they are maximally strong or can accommodate shape change,” says Marc Meyers, a professor of mechanical engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

“Straightening and stretching allow the uptake of strain without much stress increase, and sliding allows more energy dissipation during inelastic deformation.

“This reorganisation of the fibrils is responsible for blunting the stress at the tips of tears and notches.”

The new study of the skin is part of ongoing work to examine how nature achieves astounding abilities through architecture.

Print

Print