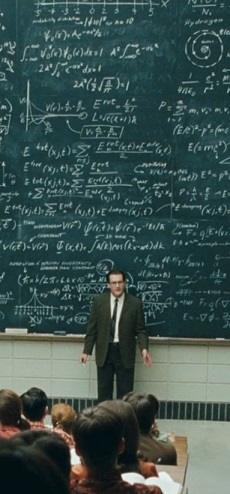

Teaching techniques trimmed from trillions

There are a truly ludicrous amount of ideas on the best teaching strategies, but a new study says trying to narrow it down to just one is not the way to go.

There are a truly ludicrous amount of ideas on the best teaching strategies, but a new study says trying to narrow it down to just one is not the way to go.

Using concrete materials, abstract approaches, giving immediate feedback, delayed feedback, and myriad more ideas exist.

Researchers scoured the educational landscape to find that because improved learning depends on so many different factors, they calculate there are more than 205 trillion instructional options available.

In a study published by the journal Science, the researchers break down exactly how complicated improving education really is when considering the combination of different dimensions — spacing of practice, studying examples or practicing procedures, to name a few — with variations in dosages and in student needs as they learn.

“There are not just two ways to teach, as our education debates often seem to indicate,” said lead author Ken Koedinger, professor of human-computer interaction at Carnegie Mellon University, director of the Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center (PSLC).

“There are trillions of possible ways to teach. Part of the instructional complexity challenge is that education is not ‘one size fits all’, and optimal forms of instruction depend on details, such as how much a learner already knows and whether a fact, concept, or thinking skill is being targeted.”

Researchers investigated existing education research to draw the conclusion that the arena is just too vast, with too many possibilities for simple studies to determine what techniques will work for which students at different learning points.

“As learning researchers, we get frustrated when our work doesn't seem to make an impact on the education system,” said Julie Booth, assistant professor of educational psychology at Temple University.

“But much of the work on these learning principles has been conducted in laboratory settings. We need to shift our focus to determine when and for whom these techniques work in real-world classrooms.”

To get a lid on instructional complexity and maximise the potential of improving research into educational practice, the team has offered five key suggestions.

For one - Research should focus on how different forms of instruction meet different functional needs, such as which methods are best for learning to remember facts, which are best for learning to induce general skills, and which are best for learning to make sense of concepts and principles.

Secondly, more experiments may be needed to determine how different instructional techniques enhance different learning functions.

Researchers should take advantage of educational technology to further understand how people learn by conducting massive online studies, which can expand the scope to use thousands of students, testing hundreds of variations of instruction at the same time.

Another suggestion is to better understand impact, a far-reaching data infrastructure in which data collected at a moment-by-moment basis, which can be linked with longer-term results.

And finally, the study suggests creating more permanent school and research partnerships to facilitate interaction between education, administration and researchers

“These recommendations are just one of the many steps needed to nail down what's necessary to really improve education and to expand our knowledge of how students learn and how to best teach them.” said Psychology Professor David Klahr.

The researchers discuss their work in more detail in the following video;

Print

Print