Some bugs evade silver

New research shows pathogens can evolve to survive nanosilver treatment.

New research shows pathogens can evolve to survive nanosilver treatment.

The study demonstrates that long-term nanosilver treatment may increase the risk of recurrent infections.

The research from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) found that pathogens that form biofilms can evolve to survive nanosilver treatment - a potent antimicrobial that is currently used in medical devices such as internal catheters, as well as wound dressings, in particular for burn wounds, to fight or prevent infections.

Nanosilver is one of the most commercialised antimicrobial nanoparticles, and has been incorporated into consumer products from personal care products, such as soaps and toothpaste, to washing machines and fridges, even children’s products, such as in kids socks to prevent odour.

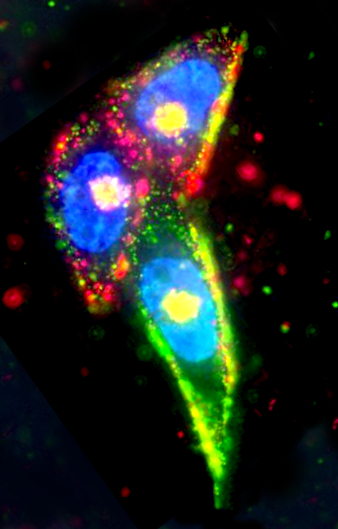

Researchers at UTS studied nanosilver adaptation phenomena in the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in its biofilm form of growth.

They observed a novel adaptation mechanism not seen in previous planktonic growth studies.

Following prolonged treatment, nanosilver killed 99.99 per cent of the bacterial population with only 0.01 per cent cells surviving for longer.

However, in a community of billions of cells, this minute fraction of ‘persisters’ was able to resume normal growth when the nanoparticle treatment stopped.

“Understanding how pathogens develop adaptation mechanisms to nanoparticles is key in our effort to overcome the phenomena, including in biofilms as the major form of growth of pathogenic bacteria. This is to protect the efficacy of important alternative antimicrobials, like nanosilver, in this era of increasing antibiotic resistance,” said lead author Dr Cindy Gunawan.

The study first author, Dr Riti Mann, said the research findings will also help develop strategies on the better management of nanoparticle use as antimicrobials, in particular those that involve long-term exposures.

“Based on this study, we recommend monitoring patients not only during, but also after prolonged use of nanoparticle treatment for safeguarding against recurrent infections,” Dr Mann said.

“The scientific evidence that bacteria can adapt to nanoparticles means we need effective regulation of the use of nanoparticles, with clear risks versus benefits assessment and clear antimicrobial targets. With limited development of new effective antibiotics over the past decades, we need to preserve the efficacy of the alternative antimicrobials to fight untreatable infections, saving lives and billions of dollars in healthcare,” said Dr Gunawan.

The bacterium used in the study, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, often attach themselves on catheter surfaces, as well as to wounds and lung linings, growing biofilms, which can be difficult to control.

The full study is accessible here.

Print

Print