Simple combination could be brain cancer breakthrough

Exciting results have come from a trial using two existing drugs to fight brain cancer.

Exciting results have come from a trial using two existing drugs to fight brain cancer.

The Swiss study explored the combination of an antidepressant and a blood thinner, which appeared to cause brain cancer cells to eat themselves.

The new evidence sheds light on the connection between tricyclic antidepressants and brain cancer.

It is an idea that has been pursued since positive results first appeared in the early 2000’s.

In a new study, researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) found that the combination of antidepressants and blood thinners fought brain cancer by increasing tumor autophagy - a process that causes the Cancer Cells to eat themselves.

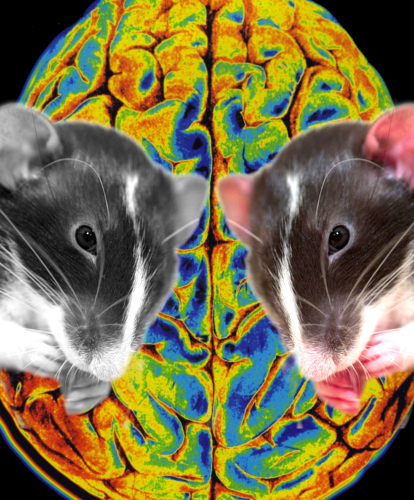

The treatment saw lifespans double for mice with the first stages of human glioblastoma, but using either drug alone had no effect.

“It is exciting to envision that combining two relatively inexpensive and non-toxic classes of generic drugs holds promise to make a difference in the treatment of patients with lethal brain cancer,” says senior study author, EPFL’s Douglas Hanahan.

“However, it is presently unclear whether patients might benefit from this treatment. This new mechanism-based strategy to therapeutically target glioblastoma is provocative, but at an early stage of evaluation, and will require considerable follow-up to assess its potential.”

Mice were given the combination therapy 5 days a week with 10-15 minute intervals between drugs.

The antidepressant was given orally, while the blood thinner (or anti-coagulant) was injected.

The resulting suggested that the drugs acted synergistically, disrupting the biological pathway that controls the rate of autophagy.

The researchers say the data showed the two drugs worked together to hyper-stimulate autophagy and cause the cancer cells to die.

“Importantly, the combination therapy did not cure the mice; rather, it delayed disease progression and modestly extended their lifespan,” Hanahan says.

“It seems likely that these drugs will need to be combined with other classes of anticancer drugs to have benefit in treating gliblastoma patients. One can also envision 'co-clinical trials' wherein experimental therapeutic trials in the mouse models of glioblastom are linked to analogous small proof-of-concept trials in GBM patients. Such trials may not be far off.”

More details are available in the full study, accessible here.

Print

Print