New antibiotic could be start of fresh wave

The first new antibiotic to be discovered in nearly 30 years could bring a ‘paradigm shift’ in the fight against drug resistance, researchers say.

The first new antibiotic to be discovered in nearly 30 years could bring a ‘paradigm shift’ in the fight against drug resistance, researchers say.

A new compound - Teixobactin - has been shown to treat common bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, septicaemia and C. diff, and its developers say it could be available within five years.

Excitingly, because of the way it was discovered, Teixobactin could even pave the way for a new generation of better antibiotics.

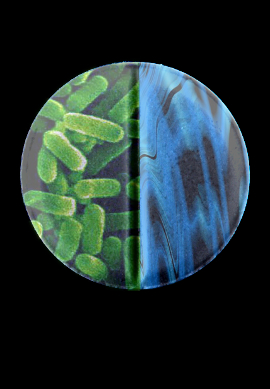

Experts believe that everyday soils are teeming with new and powerful antibiotics, developed by bacteria to fight off other microbes, but almost none of these microbes will grow in laboratory conditions.

A team from Northeastern University in Boston says it has made a breakthrough, by using an electronic chip to grow the microbes in soil and then isolate their antibiotic chemical compounds.

The first compound developed this way, Teixobactin, appears to be highly effective against common bacterial infections Clostridium difficile, Mycobacterium tuberculous and Staphylococcus aureus.

“Apart from the immediate implementation, there is also I think a paradigm shift in our minds because we have been operating on the basis that resistance development is inevitable and that we have to focus on introducing drugs faster than resistance,” Professor Kim Lewis, Director of the Antimicrobial Discovery Centre, told reporters.

“Teixobactin shows how we can adopt an alternative strategy and develop compounds to which bacteria are not resistant.”

The World Health Organisation has classified antibiotic and antimicrobial resistance as a “serious threat” to effective healthcare worldwide, but there is now hope that the new discovery could lead to new antibiotics to fight bacterial infections.

“Right now we can deliver a dose that cures mice and a variety of models of infection and we can deliver 10 mg per kg so it correlates well with human usage,” Professor Lewis said.

“The screening tool developed by these researchers could be a ‘game changer’ for discovering new antibiotics as it allows compounds to be isolated from soil producing micro-organisms that do not grow under normal laboratory conditions,” says Prof Laura Piddock, Professor of Microbiology at the University of Birmingham.

“Most antibiotics are natural products derived from microbes in the soil. The ones we have discovered so far come from a tiny subset of the rich diversity of microbes that live there,” said Prof Mark Woolhouse, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, from the University of Edinburgh.

“Lewis et al. have found a way to look for antibiotics in other kinds of microbe, part of the so-called microbial “dark matter” that is very difficult to study.

“What most excites me about the paper is the tantalising prospect that this discovery is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Print

Print