Microbes help mine rehab

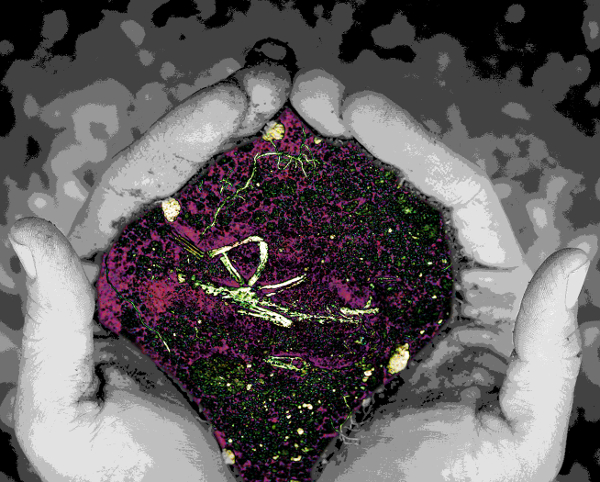

Adelaide researchers are working on a way to measure re-vegetation using microbes.

Adelaide researchers are working on a way to measure re-vegetation using microbes.

The microbe-monitoring tool could help measure the success of ecological restoration projects around the world.

University of Adelaide researchers have demonstrated that the community of bacteria present in the soil of land that had been cleared and grazed for 100 years returned to its natural state just eight years after revegetation with native plants.

The researchers sequenced the DNA in soil from samples taken across a site that featured a range of plantings between six and 10 years old.

The technique – high-throughput amplicon sequencing of environmental DNA (eDNA), otherwise known as eDNA metabarcoding – identifies and quantifies the different species of bacteria in a sample.

“Ecological restoration is an important management intervention used to combat biodiversity declines and land degradation around the world, and has very ambitious targets set under the Bonn Challenge and extended at the 2015 Paris climate talks,” says researcher Professor Andy Lowe.

“The success of these impressive goals will rely on delivering effective restoration interventions, but there are concerns that intended outcomes are not being reached. Most projects are insufficiently monitored, if at all, and where it does occur the monitoring is logistically demanding, hard to standardise, and largely discounts the microbial community.”

The researchers – students Nick Gellie and Jacob Mills, Dr Martin Breed and Professor Lowe – analysed soil samples at a restoration site at Mt Bold Reservoir in the Adelaide Hills, South Australia, and compared them with neighbouring wilderness areas as ‘reference sites’.

“We showed that the bacterial community of an old field which had been grazed for over 100 years had recovered to a state similar to the natural habitat following native plant revegetation – an amazing success story,” says Dr Breed.

“A dramatic change in the bacterial community were observed after just eight years of revegetation. The bacterial communities in younger restoration sites were more similar to cleared sites, and older sites were more similar to the remnant patches of woodland.”

The researchers say that eDNA metabarcoding holds great promise as a cost-effective, scalable and uniform ecological monitoring tool to assess the success of the restoration.

“Although still needing further development, this tool has significant scope for improving the efficacy of restoration interventions more broadly and ensuring the global targets set are achieved,” says PhD student Nick Gellie, lead author of the work.

Print

Print