Lesser-known melanoma studied

A new study has shed light on kinds of skin cancer not caused by the Sun.

A new study has shed light on kinds of skin cancer not caused by the Sun.

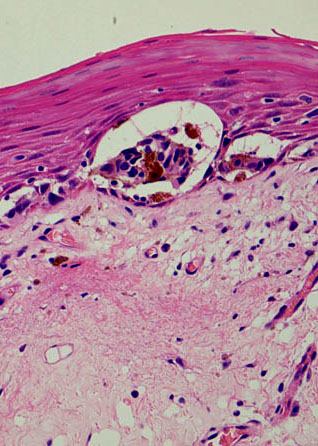

A genetic study has found that melanomas on the hands and feet (known as acral) and internal surfaces (known as mucosal) are not linked to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which could have implications for preventing and treating these forms of melanoma worldwide.

“This is by far the largest study to have looked at the whole genome in melanoma, and it has proven these less common melanomas are strikingly different in terms of their causes,” says lead author Professor Richard Scolyer.

Every year in Australia, up to 420 people are diagnosed with acral or mucosal melanomas.

They affect people of all ethnic backgrounds, and are the most common forms of melanoma in people with very dark skin. These forms of melanoma often behave more aggressively, are harder to diagnose and have a poorer outcome compared to skin melanoma.

Treatment for skin melanoma has advanced rapidly in recent years, with therapies tripling the life expectancy of some advanced melanoma patients.

“Acral and mucosal melanomas occur all over the world, but they have been even more challenging to treat than skin melanoma,” says researcher Professor Nicholas Hayward.

“Knowing these are really different diseases to skin melanoma is important for development of future therapies.”

The study also found acral and mucosal melanomas have much less gene damage compared with skin melanoma and the damage ‘footprints’ did not match those of any known causes of cancer, like sun exposure. This means new research must be aimed at discovering what causes these cancers, and what can prevent them.

While they had fewer gene drivers that could be targeted for therapy, new ones were found. Some mucosal melanomas unexpectedly had mutations in the SF3B1 and GNAQ genes, which had previously only been connected to melanoma of the eye.

Understanding which gene mutations are driving an individual tumour is the basis of personalised cancer medicine.

This is the first study to survey the entire DNA sequence of melanomas, not just the genes themselves, giving 50 times more information than in previous work.

Many genes were found to have damage in their control regions, and these may be previously unsuspected drivers of melanoma.

“This is a world-leading genetic analysis of melanoma,” explains Professor Graham Mann.

“We are working hard now to turn these discoveries about the uniqueness of acral and mucosal melanoma, and about the new control mutations, into better results for our melanoma patients.”

Print

Print