Immune blueprint uncovered

Australian researchers say they have found a molecular ‘blueprint’ for the immune system’s ability to fight disease by ‘remembering’ infections.

Australian researchers say they have found a molecular ‘blueprint’ for the immune system’s ability to fight disease by ‘remembering’ infections.

Understanding the fine detail of immunological memory potentially opens ways to improve, and to create new vaccines, and to hone treatments that use the immune system to fight disease including cancer.

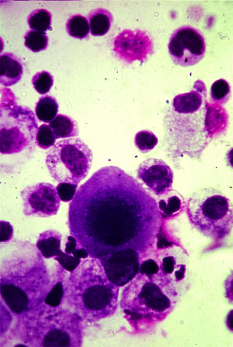

A team at Monash University has discovered that during a response to infection, the immune system’s B and T cells create memory cells, allowing it to develop immunity to future infections and also to gain protection through vaccines, which serve to mimic the sort of immunity induced by the virus or bacteria the vaccine is trying to prevent.

The study used the influenza virus to investigate how cytotoxic or killer T cells – the ‘hit men’ for fighting infection – are genetically wired to behave.

“What we found is there’s a specific sort of wiring that seems to characterise this type of immunological memory – it’s like an electrical circuit,” research leader Professor Stephen Turner said.

“We were able to identify specific ‘switches’ that are used in parts of the genome that actually give T cells their function … this means we can actually look at ways of going in and rewiring these things ourselves using novel vaccine type strategies,” he said.

The gene regulatory mechanisms that control the changes that occur in T cells during infection were previously largely unknown.

The study, which used cutting-edge gene sequencing techniques in animal models of influenza, has been published in the journal Cell Reports.

The ‘blueprint’ developed by the team could serve as a benchmark for research, and potentially be used to hone and personalise therapies, Professor Turner said.

“We can design very rational and strategic therapies such as vaccines that target particular pathogens. It might be in the context of HIV, flu or malaria, particularly when you have complex viruses that we don’t have vaccines for.”

The same mechanisms engaging T cells that are used to fight infection are used to fight cancer and in immune therapies, he said.

The study may also have implications for auto-immune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes or coeliac disease, when T cells go awry causing the immune system to attack itself.

Print

Print