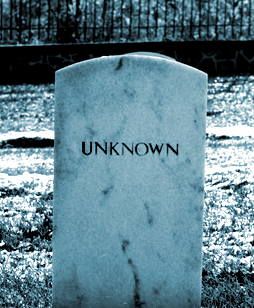

Death stats don't stack up

Australian researchers say two-thirds of deaths around the world go unreported.

Australian researchers say two-thirds of deaths around the world go unreported.

In a sobering finding for global health authorities and governments, the new investigation says the true figures of global births and deaths are almost entirely unknown.

Around the world, close to a fifth of all official causes of death are inaccurate, according to University of Melbourne Laureate Professor Alan Lopez.

Professor Lopez is at the head of a campaign to improve how countries capture civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS).

A series of research papers published in The Lancet promote the case to change CRVS systems to collect more reliable and timely data.

“Poor quality data equals poor decisions, which in turn leads to lost opportunities to improve population health,” Professor Lopez said.

The research team suggests big improvement can be made by new technology.

In remote areas where there are no doctors, CRVS improvements could see family members of deceased responding to a number of questions about symptoms experienced by the deceased.

They have developed an algorithm which uses data samples and analysis to find a most-likely cause of death, Professor Lopez said.

“In many cases, that algorithm can record cause of death more accurately than a physician,” he said.

The experts say mobile phones can help too.

“We are on the cusp of a quantum leap in using technology to greatly improve the availability and quality of birth and death data even in the poorest countries”, Professor Lopez said, adding that “mobile phones are now common virtually everywhere”.

“Accurately recording birth registration and cause of death is vitally important to leaders around the world,” he said.

“To put this in perspective, 140 countries, or 80 per cent of the world's population - do not have reliable cause of death statistics. How can you influence country and global policy and intervention programs if you don't know the underlying causes of illness and death?”

The Lancet series is broken into four articles.

The first paper looks at the current landscape of CVRS, highlighting inconsistent record-keeping worldwide, and arguing for improvements to gather better statistics to help policy makers make better decisions.

The second paper makes the case that good CRVS data is not only required for informing health policies, but that it is also actually good for health.

“Countries that have functional CRVS systems report higher life expectancies and lower maternal and infant mortality rates indicating that the availability of good birth and death data is influencing the health policies of those nations,” Professor Lopez said.

In the third paper, the authors look at the development of existing CRVS systems and their limited growth.

The authors conclude that improvements in vital statistics systems over the past four decades have been disappointingly slow, and that rapid improvement is needed.

The concluding paper challenges global health and development agencies to ensure that every birth and death is registered, and every decision-maker has detailed, continuous and locally relevant information needed to support policy and planning.

The authors say international leaders have failed over the past few decades in asking UN agencies and partners to come together to create a data-rich environment, which can produce evidence-based policy that meets the needs of a country and region.

Print

Print