Clear results in paediatric cataract trial

An international team of scientists has reported a successful outcome in trials for a new method to repair congenital cataracts.

An international team of scientists has reported a successful outcome in trials for a new method to repair congenital cataracts.

All 12 paediatric cataract patients who received new surgery to regenerate their lenses recorded superior visual function.

The regenerative technique allows surgeons to remove congenital cataracts in infants, so that their remaining stem cells can regrow functional lenses.

Congenital cataracts – lens clouding that occurs at or shortly after birth – are a significant cause of blindness in children, as they obstruct the passage of light to the retina and block visual information on its way to the brain.

Current treatment is limited by the age of the patient, and usually involves cataract surgery and corrective eyewear.

The new treatment developed by researchers at the University of California San Diego and China’s Sun Yat-sen University appears to produce many fewer surgical complications than the current standard-of-care in all 12 of the paediatric patients.

The technique relies on the regenerative potential of endogenous stem cells. Unlike other stem cell approaches that involve creating stem cells in the lab and introducing them back into the patient, endogenous stem cells are stem cells already naturally in place at the site of the injury or issue.

In the case of the human eye, lens epithelial stem cells (LECs) generate replacement lens cells throughout a person’s life, but their production declines with age.

Current cataract surgeries remove most LECs from within the lens, and so the leftover cells generate disorganised regrowth in infants, with no useful vision.

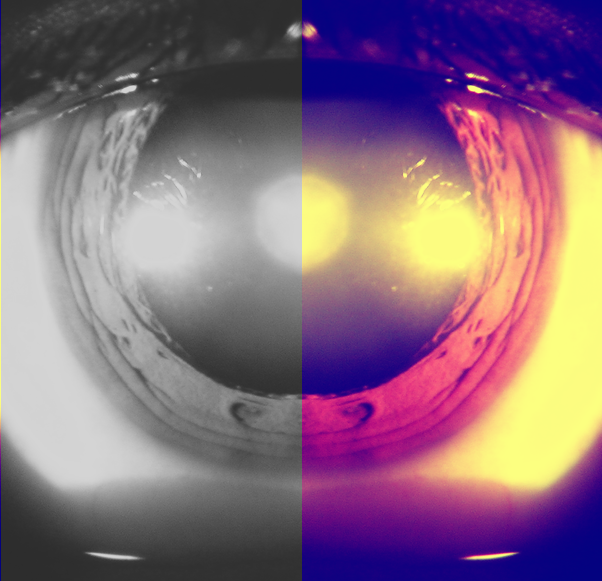

Now, researchers can use the new, minimally-invasive surgery method to preserves the integrity of the regenerative potential LECs in the lens capsule – a membrane that helps give the lens its shape – and stimulate them to grow and form a functional new lens.

After a series of animal tests, a human trial was undertaken involving 12 infants under the age of 2 treated with the new method and 25 similar infants receiving current standard surgical care.

The latter control group experienced a higher incidence of post-surgery inflammation, early-onset ocular hypertension and increased lens clouding.

The scientists reported fewer complications and faster healing among the 12 infants who underwent the new procedure and, after three months, a clear, regenerated biconvex lens in all of the patients’ eyes.

The team is now looking to expand its work to treating age-related cataracts. Age-related cataracts are the leading cause of blindness in the world, affecting more than 94 million people worldwide.

“We believe that our new approach will result in a paradigm shift in cataract surgery and may offer patients a safer and better treatment option in the future,” said Kang Zhang, MD, PhD, chief of Ophthalmic Genetics, founding director of the Institute for Genomic Medicine and co-director of Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering at the Institute of Engineering in Medicine, both at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Print

Print