Chinese lab breeds two-mum mice

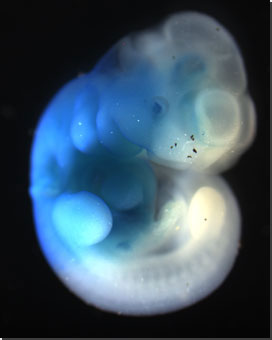

Chinese researchers have produced healthy mice with two mothers.

Chinese researchers have produced healthy mice with two mothers.

Experts at the Chinese Academy of Sciences bred the mice with two mothers (bimaternal) by altering stem cells from a female mouse and injecting them into the eggs of another.

In mammals, because certain maternal or paternal genes are shut off during germline development, so offspring that do not receive genetic material from both a mother and a father might experience developmental abnormalities or might not be viable.

Previous studies have produced bimaternal mice by deleting these imprinted genes from immature eggs, but these tended to display defective features, and the method itself was very impractical and hard to use.

To produce their healthy bimaternal mice, researcher Qi Zhou, co-senior author Baoyang Hu, co-senior author Wei Li, used haploid embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which contain half the normal number of chromosomes and DNA from only one parent.

The researchers created the mice with two mothers by deleting three imprinting regions of the genome from haploid ESCs containing a female parent's DNA and injected them into eggs from another female mouse.

They produced 29 live mice from 210 embryos. The mice were normal, lived to adulthood, and had babies of their own.

“We found in this study that haploid ESCs were more similar to primordial germ cells, the precursors of eggs and sperm. The genomic imprinting that's found in gametes was ‘erased’,” said Hu.

Twelve live, full-term mice with two genetic fathers were produced using a similar but more complicated procedure.

Those embryos were transferred along with placental material to surrogate mothers, who carried them to term, but the pups only survived 48 hours after birth. The team plans to find ways to extend the lifetimes of mice with two fathers.

Overall, they say the work suggests that some significant barriers to reproduction can be overcome using stem cells and targeted gene editing.

Professor Bob Williamson - chair of the board of Stem Cells Australia – says that reproducing the same technique in humans is a very long way off, but warns that it is something society will have to deal with soon.

“If the research is reproducible, and also works in humans, it still has to be shown to be safe,” he said.

“In Australia, there are both legal prohibitions and ethics committees that would ensure these techniques could not be used for human reproduction.

“The experiments are, however, important, because they may shine a light on some causes of serious handicap in children.

“This research does illustrate how quickly research with stem cells is moving, and everyone, whether they feel enthusiastic or worried about these new techniques, will be thinking; ‘Surely, we should have an ethics group that studies this, and can advise the Government if these changes are moving too far, too fast’.”

Print

Print