Cells traced to first split

Researchers say they can now trace the cells of a 78-year-old back to where it all began.

Researchers say they can now trace the cells of a 78-year-old back to where it all began.

An international team has retraced the cells of a 78-year-old woman back to the first cell division that created her body.

The findings provide new insights into how the human body develops from one cell into trillions, and the genetic mutations that cells pick up along the way.

The new view comes from two studies by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge and their collaborators.

The studies are the first to analyse somatic mutation in normal tissues across multiple organs within and between individuals. Researchers were able to retrace human development, including in a 78-year old individual, all the way back to the first cell division, as well as confirm that the mutation rate in the germline cells is much lower than in the other tissues of the body.

The findings should help to establish baselines for human development and how mutations are acquired throughout life, in both the cells of the body and the genetic code that is passed on to the next generation.

Knowing what ‘normal’ development and ageing looks like will in turn help to better understand the onset of disease.

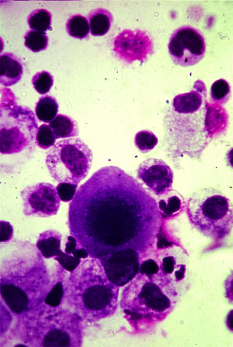

The findings were achieved by taking micro-biopsies of just a few hundred cells, which are then genome sequenced to an incredibly high degree of accuracy.

From the very first cell division, an individual’s cells experience damage to their genome. Most of this damage is repaired by the cell, but some changes to the letters of DNA, known as somatic mutations, persist. Through cell division, these mutations are then passed on to the next generation of cells by progenitor cells.

When two cells share the same mutations, this implies a shared ancestry and these markers can be used to trace development back through time.

The genetic code that is passed on via sperm and egg cells during reproduction, known as the germline, has long been thought to be protected from the mutational processes that occur in the rest of the body as it ages.

This helps to ensure that individuals start life with a genome that is ‘intact’, or free from the mutations acquired by the parents during their lives.

“By examining the history of each cell, we’ve been able to retrace the development of a 78-year-old person all the way back to the first cell division,” says Dr Tim Coorens, a first author of the studies.

“It was surprising to find how much variation there was in human development between individuals, and especially between tissues in the same person.

“It’s not as straightforward as the same set of cells contributing to the heart or kidneys, say, in every person. What our study makes clear is that human embryology is not set in stone.”

The studies that informed the findings are accessible here, here and here.

Print

Print