Tasmania reef crew returns

A search of undersea mountains in marine parks off Tasmania has uncovered new reefs and dozens of unnamed species.

A search of undersea mountains in marine parks off Tasmania has uncovered new reefs and dozens of unnamed species.

Scientists and park managers have returned from a four-week survey of ‘seamounts’ on CSIRO research vessel Investigator.

The unusual cluster of more than 100 seamounts is world-renowned for its deep-sea corals and diverse marine life.

For the first time, new technologies enabled scientists to look at rocky habitats between the seamounts that support deep-sea corals, in particular the main reef-building stony coral, Solenosmilia variabilis.

“We surveyed 45 seamounts in total, and criss-crossed seven in detail completing a total of 147 transects covering 200 kilometres in length,” CSIRO voyage chief scientist Alan Williams said.

“We ‘flew’ our high-tech camera system two metres above the seafloor in depths to 1900 metres, collecting 60,000 stereo images and some 300 hours of video for analysis.

“While it will take months to fully analyse the coral distributions, we have already seen healthy deep-sea coral communities on many smaller seafloor hills and raised ridges away from the seamounts, to depths of 1,450 metres.

“This means that there is more of this important coral reef in the Huon and Tasman Fracture marine parks than we previously realised.”

Live imagery from the deep-tow camera systems revealed dense coral reefs, as well as hundreds of animals including feathery, solitary soft corals, tulip-shaped glass sponges and crinoids attached to the seafloor. Their colours ranged from delicate creams and pinks to striking purples, bright yellows and golds.

Bioluminescent squids, ghost sharks, deep-water sharks, rays, orange roughy, oreos and basketwork eels were also seen near the seafloor. And from above the water, an observation team collected data on more than 40 species of seabirds, and several whale and dolphin species.

A small net was used to collect biological samples for identification, and many new species were found, as is expected in such remote environments. A high proportion of the mollusc species collected were unknown.

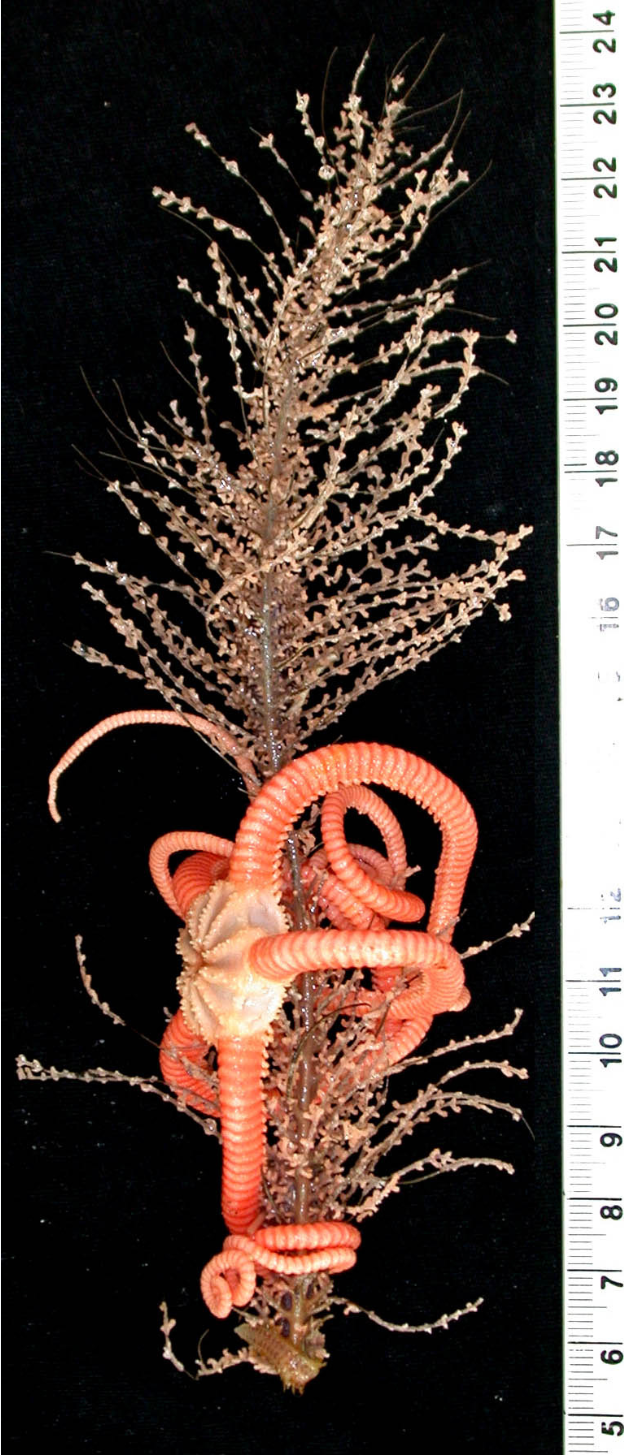

There were many instances of mutually beneficial relationships among the samples, with brittlestars curled around corals, polychaete worms tunnelling inside corals, and corals growing on the surface of shells.

“We now have a huge body of data on the animals that live on seamounts and how their communities change with depth, and have a much broader picture of what lives on habitats adjacent to the seamounts,” Dr Williams said.

“We have identified the precise depth range in which the diverse Solenosmilia community thrives. On the larger seamounts which peak in 1000–1250 m depth below the sea surface, corals dominate the top 100–200 metres.

“Our detailed sampling was on seamounts that were previously impacted by bottom fishing but have been protected since for more than 20 years.

“While we saw no evidence that the coral communities are recovering, there were signs that some individual species of corals, featherstars and urchins have re-established a foothold.”

Print

Print