Ancestors in microscope "dust"

What were once considered random dust specks on microscope slides turn out to be our ancient, spineless ancestors.

What were once considered random dust specks on microscope slides turn out to be our ancient, spineless ancestors.

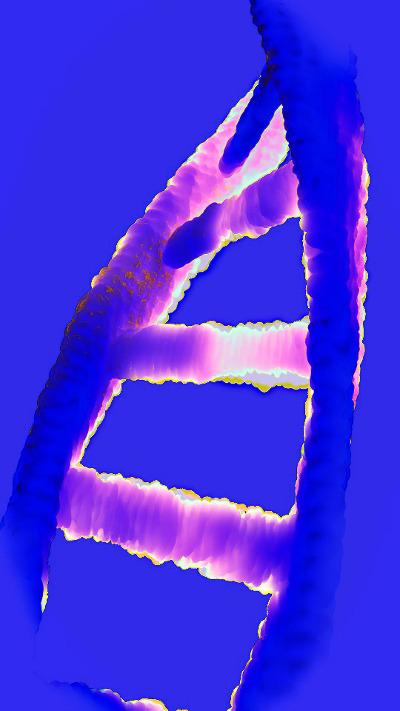

Scientists have discovered that tiny ‘microchromosomes’ in birds and reptiles, initially thought to be dust, are linked to an animal ancestor that lived 684 million years ago.

In fact, a new study shows they are the building blocks of all animal genomes, but underwent “dizzying rearrangement” in mammals, including humans.

Professor Jenny Graves at La Trobe University made the discovery by lining up the DNA sequence of microchromosomes that huddle together in the cells of birds and reptiles.

When these little microchromosomes were first seen under the microscope, scientists thought they were just specks of dust among the larger bird chromosomes, but are actually proper chromosomes.

Professor Graves says that, using advanced DNA sequencing technology, scientists can at last sequence microchomosomes end-to-end.

“We lined up these sequences from birds, turtles, snakes and lizards, platypus and humans and compared them,” Professor Graves said.

“Astonishingly, the microchromosomes were the same across all bird and reptile species. Even more astonishingly, they were the same as the tiny chromosomes of Amphioxus – a little fish-like animal with no backbone that last shared a common ancestor with vertebrates 684 million years ago.”

Professor Graves said in marsupial and placental mammals these ancient genetic remnants are split up into little patches on our big, supposedly normal, chromosomes.

“The exception is the platypus genome, in which the microchomosomes have all fused together into a few large blocks that reflect our oldest mammal ancestor,” she said.

Professor Graves said the findings highlight the need to rethink how we view the human genome.

“Rather than being ‘normal’, chromosomes of humans and other mammals were puffed up with lots of ‘junk DNA’ and scrambled in many different ways,” Professor Graves said.

“The new knowledge helps explain why there is such a large range of mammals with vastly different genomes inhabiting every corner of our planet.”

Print

Print