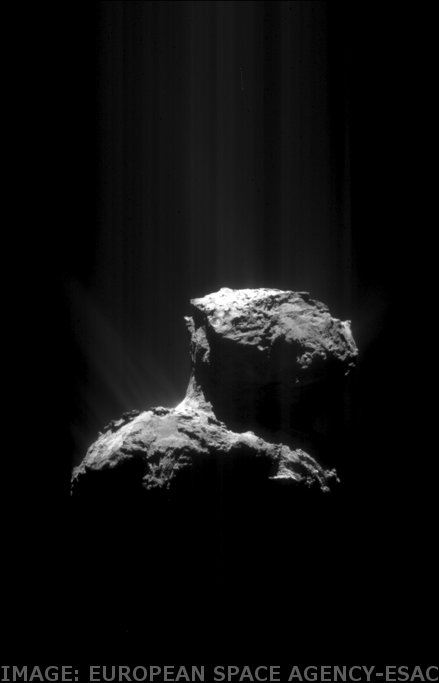

Surprising find flies off 67P

The Rosetta mission has made the surprising discovery that there is oxygen on Comet 67P, around which the ESA probe is orbiting.

The Rosetta mission has made the surprising discovery that there is oxygen on Comet 67P, around which the ESA probe is orbiting.

Details of the discovery have been published in the journal Nature, and could provide new clues about the cosmic conditions when the Earth, Sun and solar system were born, about 4.6 billion years ago.

“This is the first comet that we've found which has molecular oxygen,” said Dr André Bieler, researcher at the University of Michigan.

“The detection of molecular oxygen is new and very surprising. This was a very strong signal indicating that we found a lot of it.”

The cloud of gas – known as a ‘coma’ - surrounding a comet is usually made up of water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, and trace amounts of other chemicals.

Dr Bieler and his research team say the ratio of molecular oxygen to water in Comet 67P’s coma is about 3.8 per cent.

“We detected this molecular oxygen very early on in the mission - more than a year ago - and were very surprised,” Dr Bieler said.

“No-one expected this to happen so we didn't want to publish anything right away.

“We decided to keep monitoring this molecular oxygen signature until we were sure we understood what was happening.”

Dr Bieler says the big question for the team know is to find out why Comet 67P contains molecular oxygen.

Given that comets lose between one and 10 metres of their surface material during each orbit around the Sun, and Comet 67P has been around for quite a while, the continued presence of oxygen suggests it is either constantly produced on the surface or is embedded throughout its structure.

Dr Bielier say the experts are leaning towards the first option.

The research team had speculated that molecular oxygen is being generated by energy from the Sun changing the molecular structure of water molecules on the surface.

But because the ratio of oxygen to water was even across the comet, not just the parts facing the Sun, the oxygen is embedded throughout the whole body of comet.

Molecular oxygen has previously been found in star-forming clouds that are slightly warmer than their usual temperature of between minus 253 to minus 243 degrees Celsius.

“This could mean that our solar system was not very typical in how it formed, but had warmer temperatures giving it an elevated abundance of molecular oxygen in a gaseous phase, which was later incorporated into the comet,” Dr Bieler said.

Dr Bieler’s team is now working to find out if molecular oxygen has been detected in other comets.

“We're examining some 30-year-old data from the Giotto spacecraft's encounter with Comet Halley to see if we can find hints of molecular oxygen,” he said.

“Those instruments won't able to resolve molecular oxygen, but maybe we'll find something that will indicate its presence in some indirect way.”

Print

Print