Bugs live after ages on ice

Tardigrades may have lost their title as the world’s most resilient beasts.

Tardigrades may have lost their title as the world’s most resilient beasts.

Tiny tardigrades, sometimes known as water bears, are amazingly tough and can survive being frozen for decades, only to pop back up and go on living.

However, an even tinier bug is showing an even greater level of tenacity.

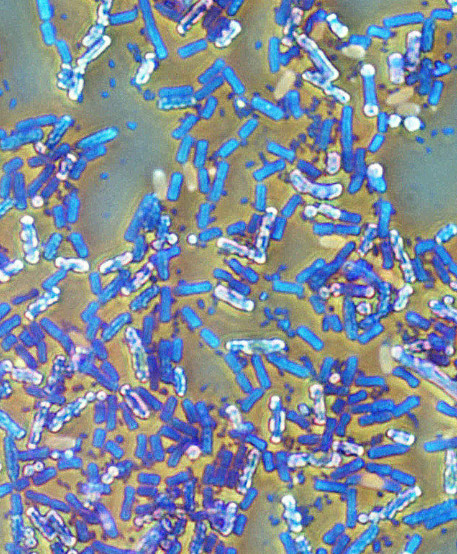

Microscopic animals called Bdelloid rotifers have been revived by international scientists after being frozen in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years.

“Our report is the hardest proof as of today that multicellular animals could withstand tens of thousands of years in cryptobiosis, the state of almost completely arrested metabolism,” says researcher Stas Malavin of the Soil Cryology Laboratory at the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science in Pushchino, Russia.

The Russian lab specialises in isolating microscopic organisms from the ancient permafrost in Siberia. To collect samples, they use a drilling rig in some of the most remote Arctic locations.

They have previously identified many single-celled microbes, mosses and plants that have been regenerated after many thousands of years trapped in the ice.

Now, the team adds rotifers to the list of organisms with a remarkable ability to survive, seemingly indefinitely, in a state of suspended animation beneath the frozen landscape.

The researchers used radiocarbon-dating to determine that some rotifers they recovered from the permafrost were about 24,000 years old.

Once thawed, the rotifer, which belongs to the genus Adineta, was able to reproduce by cloning itself in a process known as parthenogenesis.

To follow the process of freezing and recovery of the ancient rotifer, the researchers froze and then thawed dozens of rotifers in the lab.

The studies showed the rotifers could withstand the formation of ice crystals that happens during slow freezing. It suggests they have some mechanism to shield their cells and organs from harm at exceedingly low temperatures.

“The takeaway is that a multicellular organism can be frozen and stored as such for thousands of years and then return back to life - a dream of many fiction writers,” Dr Malavin says.

“Of course, the more complex the organism, the trickier it is to preserve it alive frozen and, for mammals, it's not currently possible. Yet, moving from a single-celled organism to an organism with a gut and brain, though microscopic, is a big step forward.”

It is not yet clear what it takes to survive on ice for even a few years and whether the leap to thousands makes much difference, he says.

Ultimately, the researchers want to learn more about the biological mechanisms that allow the rotifers to survive. They hope that insights from these tiny animals will offer clues as to how better to cryo-preserve the cells, tissues, and organs of other animals, including humans.

Print

Print