Arctic cliffs' size dives

The permafrost cliffs of Eastern Siberia are becoming much less permanent, with new evidence of thawing at an ever-increasing rate.

The permafrost cliffs of Eastern Siberia are becoming much less permanent, with new evidence of thawing at an ever-increasing rate.

German scientists have used 40 years worth of aerial and ground data to measure the decline of the icy cliffs in the Arctic.

According to an ongoing research project, the reason for the increasing rate of erosion is rising summer temperatures in the Russian permafrost regions combined with the effect of the retreat of Arctic sea ice.

German researchers say the natural coastal protection recedes more and more each year as waves work to undermine the shores.

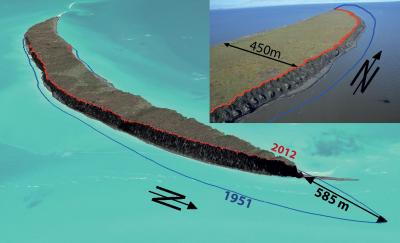

The land surface is reportedly sinking too, causing a very real threat to inhabitants of the small island of Muostakh. Located east of the Lena Delta, the tiny atoll is especially affected by the observed changes.

Experts fear that Muostakh might disappear altogether, should the loss of land continue.

For the researchers from the German government-funded PROGRESS project, the interconnectivity is clear - the warmer the east Siberian permafrost regions become, the quicker the coast erodes.

“If the average temperature rises by 1 degree Celsius in the summer, erosion accelerates by 1.2 meters annually,” says geographer Frank Günther, who has published articles on the causes of the coastal breakdown in Eastern Siberia.

The increase in temperature can create compounding consequences. Where a thick layer of sea ice used to protect the frozen soil year round, it now recedes for increasing periods of time during the summer months.

There has been an increase in the number of summer days on which the sea ice in the southern Laptev Sea vanishes completely.

“During the past two decades, there were, on average, fewer than 80 ice-free days in this region per year. During the past three years, however, we counted 96 ice-free days on average. Thus, the waves can nibble at the permafrost coasts for approximately two more weeks each year,” explains AWI permafrost researcher Paul Overduin.

Waves are observed to dig deep recesses into the base of the high frozen coasts. As a result, undermined slopes break off bit by bit.

During the past 40 years, the coastal areas surveyed retreated on average 2.2 meters per year.

“During the past four years, this value has increased at least 1.6 times, in certain instances up to 2.4 times to reach 5.3 meters per year,” says Paul Overduin.

For the little island of Muostakh east of the harbour town of Tiksi, the erosion may well spell the end of its time in the sun.

“In fewer than one hundred years, the island will break up into several sections, and then it will disappear quickly,” predicts Frank Günther.

Observations have shown a 34 per cent loss in volume.

“If one bears in mind that it took tens of thousands of years for the island to form through sedimentary deposition, then its disintegration is proceeding at a very rapid pace,” says Paul Overduin.

The recent reports have been made as part of the ongoing PROGRESS (Potsdam Research Cluster for Georisk Analysis, Environmental Change and Sustainability) initiative, more information is available here.

Print

Print