Ancient teeth give climate data

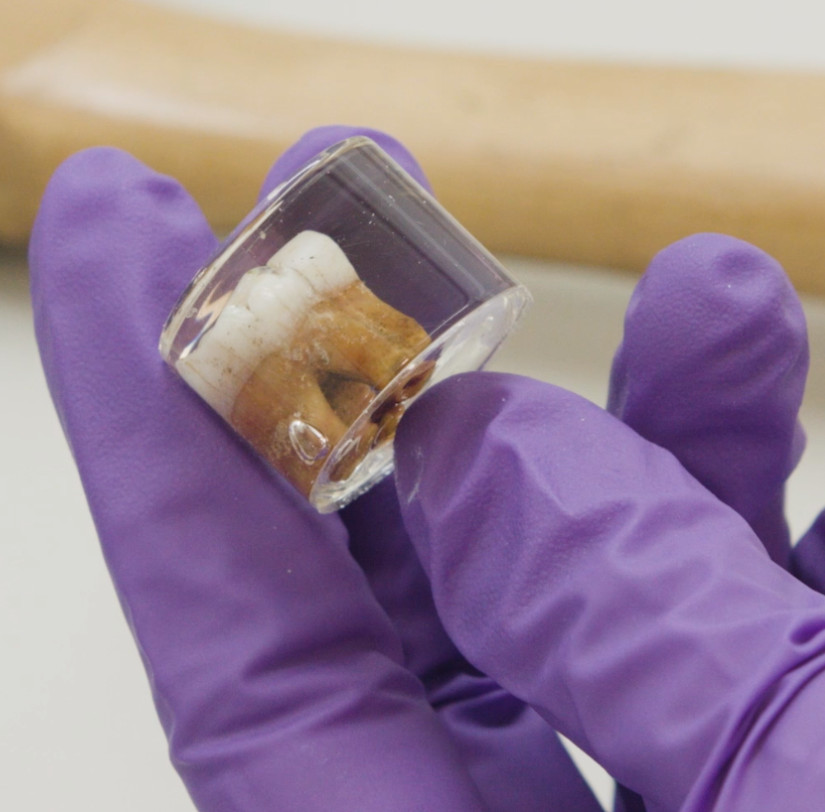

A set of 250,000-year-old teeth have revealed unprecedented detail about ancient children.

A set of 250,000-year-old teeth have revealed unprecedented detail about ancient children.

The study has revealed the oldest exposure to lead and the first natural weaning from breastfeeding in a fossil hominin (humans and their close ancestors and relatives).

Experts say it is a major breakthrough in the reconstruction of ancient climates - a significant factor in human evolution, as temperature and precipitation cycles influenced the landscapes and food resources our ancestors relied on.

Thin sections of teeth from two Neanderthals and one modern human (5000 years ago) from a French archaeological site were imaged with polarised light microscopy to document each day of their childhood growth.

Teeth have biological rhythms akin to tree rings, but on a much finer scale.

The team then used a sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP) at ANU to collect information on oxygen variation during three years of tooth growth in each youngster.

“This allowed us to relate their development to ancient seasons, revealing that one Neanderthal was born in the spring, and that both Neanderthal children were more likely to be sick during colder periods,” says Associate Professor Tanya Smith.

“At the time they grew up, 250,000 years ago, this region of southeast France was much more seasonal than it is today.”

The teeth sections also travelled to the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, where experts in environmental health mapped the concentrations of metal in the teeth, including barium, a marker of milk consumption.

The team was surprised to discover that the two Neanderthal children either ingested or inhaled lead during their childhood, representing the oldest documented lead exposure in any hominin (humans and their close ancestors and relatives).

This occurred multiple times during the cooler seasons, potentially happening in caves as underground lead sources have been found within 25km of the archaeological site.

The tiny amount of barium also showed that one Neanderthal appears to have breastfed for 2.5 years, weaning in the fall. This individual survived infancy but was unlikely to have reached adulthood.

Professor Smith and her team are keen to explore the childhoods of other hominins using this novel paleobiological approach, as many questions remain about why humans survived while our many evolutionary cousins, including the Neanderthals, were not so lucky.

Print

Print